Being born somewhere is not just a stroke of fate, with chance handing out favour to some and disaster to others. Initially, we are a product, the result of a chromosome cross between particular genitors, disposing of their own physical and intellectual characteristics. First of all, we belong to this biological association. And thus we become part of a significant history. In the frantic race towards the egg cell, one sperm may win over hundreds of million others, but each one carries the possibility of a particular being. How could one imagine, without feeling the vertigo of infinity, that no gamete-ovum crossing has reportedly ever given an identical result ever since mankind is mankind. A biologist would probably find this astonishment puerile in regard to the natural chemical attraction process, but personally, as a profane observe and ignorant artist, it leaves me dumbstruck. Or, as one pertinent internet user writes on Facebook: “If one day you’re feeling low, remember that you’re a winning sperm!” Perhaps if each one of us were conscious of this miraculous privilege, we would look at ourselves differently. Everything thus differs. Each expression of life is unique, and what more is, it is transitory. Is it not just one string of fleeting images, impregnated by certain light, certain character and a certain mood, to the point of questioning what this perennial and familiar identity that we pretend to possess really is? What image is ours? The question is daring, but necessary for the subject we want to treat. To me, it is not about stirring up some sort of metaphysical controversy, but only to approach the question very humbly, from the simple point of view of a photographer. I would like to start with a revealing experiment  in which psycho-sociologist Fabienne Bernard and I participated. We were helping companies who experienced malfunctioning due to incomprehension in between their staff. The idea was to fight against fixed ideas and narrow-minded simplification – which are by the by largely the root cause in most conflicts – by allowing each participant to produce the photographic image for each of their colleagues, as they saw them. The result: no portrait was like another. The individual was shattered into different representations. Both disturbed and enriched by the plurality of visions. I have studied shamanic rituals for years, and I would say that this is exactly how shamans operate. First, they attempt, in one way or another, to destabilise the person to reconstruct them afresh through a purifying, acting force. Our little photo session had the same effect on this disunited team. It loosened up the situation enough for the coaches to build new, more stable foundations for the human relations. The evident conclusion is that we often see ourselves only through habit. We are stuck in clichés and stereotypes that protect and reassure us. We base ourselves on a certain image of ourselves and others. We’re looking, but we don’t see! In psychology, you call this the halo effect. It brings out the inhibitive part of our background, in the way that we sift through information via what we have learned so far. If our vision forces the brain to make abstraction of continuous change in order to extract what is necessary to categorise objects, it also sacrifices all material that seems unnecessary, but is, in reality, conveyor of information that can renew our vision. We should listen to Merleau Ponty who writes that “real philosophy is to re-learn to see the world.” As we naturally have this visual predisposition since childhood, we think that

in which psycho-sociologist Fabienne Bernard and I participated. We were helping companies who experienced malfunctioning due to incomprehension in between their staff. The idea was to fight against fixed ideas and narrow-minded simplification – which are by the by largely the root cause in most conflicts – by allowing each participant to produce the photographic image for each of their colleagues, as they saw them. The result: no portrait was like another. The individual was shattered into different representations. Both disturbed and enriched by the plurality of visions. I have studied shamanic rituals for years, and I would say that this is exactly how shamans operate. First, they attempt, in one way or another, to destabilise the person to reconstruct them afresh through a purifying, acting force. Our little photo session had the same effect on this disunited team. It loosened up the situation enough for the coaches to build new, more stable foundations for the human relations. The evident conclusion is that we often see ourselves only through habit. We are stuck in clichés and stereotypes that protect and reassure us. We base ourselves on a certain image of ourselves and others. We’re looking, but we don’t see! In psychology, you call this the halo effect. It brings out the inhibitive part of our background, in the way that we sift through information via what we have learned so far. If our vision forces the brain to make abstraction of continuous change in order to extract what is necessary to categorise objects, it also sacrifices all material that seems unnecessary, but is, in reality, conveyor of information that can renew our vision. We should listen to Merleau Ponty who writes that “real philosophy is to re-learn to see the world.” As we naturally have this visual predisposition since childhood, we think that  we perfectly understand the subject. And we think that we do not need to challenge it. However, as we have not been taught how to read them, images confront us without us being able to decode them in an appropriate way. And the enigmas hidden in their appearance can only escape us. Seeing is a process far more complex than we supposed as late as a decade ago. It is now believed that several areas of the brain interact simultaneously, both with capture and understanding. The experiments conducted by Professor Michael Herzog show that between what we actually see and what we think we see, there can be vast variation. We don’t actually see things as they are. We stubbornly classify and file them even before we ask ourselves what their meaning is. It is about knowing how to see in the sense that Oscar Wilde had in mind when he said that “one does not see anything until one sees its beauty.” We could perhaps agree with Alain Beltzung, author of Traité de Regard, that “going back to the mystery of vision is first and foremost an artistic process.” And yet, teaching visual arts is pitifully relegated to the attics of education. So it is not surprising that only very few people have, during their lifetime, had a real opportunity to learn how to see correctly. But we know to what point the shape of reality is intricately linked with our way of observing! Keeping or rejecting is the very principle of vision and perhaps even that of life. The eye never rests! How much data do we memorise out of the mass of new information that we perceive in each moment? We can readily agree that the more we are familiar with an image, the more its appearance, with the patina of habit, seems trite. It loses its sense through having gained too much of it! By abandoning our faculties for sensorial learning, with which we explore the

we perfectly understand the subject. And we think that we do not need to challenge it. However, as we have not been taught how to read them, images confront us without us being able to decode them in an appropriate way. And the enigmas hidden in their appearance can only escape us. Seeing is a process far more complex than we supposed as late as a decade ago. It is now believed that several areas of the brain interact simultaneously, both with capture and understanding. The experiments conducted by Professor Michael Herzog show that between what we actually see and what we think we see, there can be vast variation. We don’t actually see things as they are. We stubbornly classify and file them even before we ask ourselves what their meaning is. It is about knowing how to see in the sense that Oscar Wilde had in mind when he said that “one does not see anything until one sees its beauty.” We could perhaps agree with Alain Beltzung, author of Traité de Regard, that “going back to the mystery of vision is first and foremost an artistic process.” And yet, teaching visual arts is pitifully relegated to the attics of education. So it is not surprising that only very few people have, during their lifetime, had a real opportunity to learn how to see correctly. But we know to what point the shape of reality is intricately linked with our way of observing! Keeping or rejecting is the very principle of vision and perhaps even that of life. The eye never rests! How much data do we memorise out of the mass of new information that we perceive in each moment? We can readily agree that the more we are familiar with an image, the more its appearance, with the patina of habit, seems trite. It loses its sense through having gained too much of it! By abandoning our faculties for sensorial learning, with which we explore the  surroundings as children, for off-the-peg thinking, we deprive ourselves of all possibilities to investigate our own world. The fact that censure commands our inner self and blocks the access to this somewhere or something bright, seems to be expressed as emotion. “In each moment there is infinitely more than we can see,” noted Sartre. Finding our way back to a fresh vision remains possible. The first step would be to clean up our mental certitudes. In the present, you would have to be open and receptive to other perceptions so that new comprehension can blossom. You would have to always consider things – including the most commonplace – as if you had never seen them before in order to provoke renewal, or even wealth, from them. You would have to decentre yourself to better withdraw affection from the subject, relativity from the absolute, novelty from the familiar and, finally, beauty from banality. “Nobody knocks on the door of the Muses in cold blood,” said Platon to illustrate the importance of feelings in the process of invention. And do we actually see ourselves twice in the same way apart from through convention, comfort, laziness or fear? Each being, like each object, may seem perpetuated in its configuration, but is part of a continuous movement that only the temporality of memory can transform into something permanent. “Art does not reproduce the visible, rather it makes visible,” claimed Paul Klee. Each circumstance of life produces an opportunity to detect what is at the source of our reactions and our motivation. Vision – such as we foresee it – must generate a neuralgic interpretation able to produce a more creative vision, bearer of magic and amazement. Learning to

surroundings as children, for off-the-peg thinking, we deprive ourselves of all possibilities to investigate our own world. The fact that censure commands our inner self and blocks the access to this somewhere or something bright, seems to be expressed as emotion. “In each moment there is infinitely more than we can see,” noted Sartre. Finding our way back to a fresh vision remains possible. The first step would be to clean up our mental certitudes. In the present, you would have to be open and receptive to other perceptions so that new comprehension can blossom. You would have to always consider things – including the most commonplace – as if you had never seen them before in order to provoke renewal, or even wealth, from them. You would have to decentre yourself to better withdraw affection from the subject, relativity from the absolute, novelty from the familiar and, finally, beauty from banality. “Nobody knocks on the door of the Muses in cold blood,” said Platon to illustrate the importance of feelings in the process of invention. And do we actually see ourselves twice in the same way apart from through convention, comfort, laziness or fear? Each being, like each object, may seem perpetuated in its configuration, but is part of a continuous movement that only the temporality of memory can transform into something permanent. “Art does not reproduce the visible, rather it makes visible,” claimed Paul Klee. Each circumstance of life produces an opportunity to detect what is at the source of our reactions and our motivation. Vision – such as we foresee it – must generate a neuralgic interpretation able to produce a more creative vision, bearer of magic and amazement. Learning to  examine what is given, and not necessarily what deceives, will necessarily lead to unprecedented, new comprehension. Matisse said: “Seeing alone is a creative process that requires effort”. Delimiting, cutting out and subtracting an object from the confusion in order to give it its own universe is the very base of photographic vision. Like a child, the photographer observes, is surprised, immerses himself… and feels until he is no more than a vision, capable of experiencing and welcoming the improbable. In the end, it is less about photographing things than sketching his own universe, representing himself. If he can be entirely certain of knowing nothing, at least he can claim to be an eye that sees. Nature always proffers an overall view full of pictures ready to be taken. Photography is an easy means for man to represent all that he sees with his eyes. But putting an eye to the viewfinder does not make an artist of everyone taking pictures. Taking your small piece of emotion in the large offer of the world to bring it closer to you, to the level of intuition, requires an initiation in the ability to make the most of both space and time. This ability to, in effect, divide reality into images, personifies, to Spinoza, the highest form of intelligence. It is what Gaspard-Félix Tournachon (better known as Nadar) demonstrates: “If the theory of photography can be learnt in an hour; the first practical steps in a day, what you cannot teach, I’m telling you,” he assured, “is the feeling for light (…). What is even more impossible to teach, is the moral intelligence of the subject, this quick tact that enables communication with the model.” The faces I have managed to photograph in the world do not tell anything else but an instant of

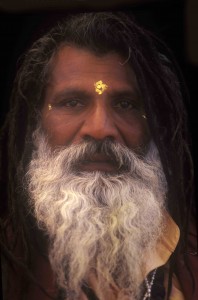

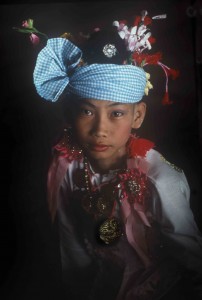

examine what is given, and not necessarily what deceives, will necessarily lead to unprecedented, new comprehension. Matisse said: “Seeing alone is a creative process that requires effort”. Delimiting, cutting out and subtracting an object from the confusion in order to give it its own universe is the very base of photographic vision. Like a child, the photographer observes, is surprised, immerses himself… and feels until he is no more than a vision, capable of experiencing and welcoming the improbable. In the end, it is less about photographing things than sketching his own universe, representing himself. If he can be entirely certain of knowing nothing, at least he can claim to be an eye that sees. Nature always proffers an overall view full of pictures ready to be taken. Photography is an easy means for man to represent all that he sees with his eyes. But putting an eye to the viewfinder does not make an artist of everyone taking pictures. Taking your small piece of emotion in the large offer of the world to bring it closer to you, to the level of intuition, requires an initiation in the ability to make the most of both space and time. This ability to, in effect, divide reality into images, personifies, to Spinoza, the highest form of intelligence. It is what Gaspard-Félix Tournachon (better known as Nadar) demonstrates: “If the theory of photography can be learnt in an hour; the first practical steps in a day, what you cannot teach, I’m telling you,” he assured, “is the feeling for light (…). What is even more impossible to teach, is the moral intelligence of the subject, this quick tact that enables communication with the model.” The faces I have managed to photograph in the world do not tell anything else but an instant of  communion. They are flow, current and vibration before being portraits. The black background that I resolutely use as a unity of place and time has a dual vocation. Aesthetically pleasing, it is also a congenital attachment to the Flemish baroque paintings, in the days when artists applied themselves to draw the faces of the jet-set as lifelike as possible, in order to transmit their referential image to posterity. Symbolic, it represents the mysterious darkness from which we appear and to which we will return after having taken forms. Not just one form, but an infinity. A quantity of fleeting appearances. Temporary expressions of one single reality that changes physiognomy after a metamorphosis of the identical. Behind the painted faces, the made-up faces, the adorned faces, the tattooed faces… stand people who are close to us, individuals driven by the same emotions. Beneath the cultural signs and marks of belonging — that first capture our attention by their exotic load — spring an ineffable sense of unity. Signs can vary; the signified remains the same from one society to another. Alongside the portrayal, there is a constant, as if beyond the inclinations inherent to space and time, there is a desire of being, serving an agreement [perhaps objective, perhaps magical] through which everything seems connected. Could it be that something evoked by Paul Ricoeur, making human beings identify as human, through an ethical desire, and which should earn them unconditional respect, no matter what their age, gender, religion, social condition or ethnic origins? An occidental idea of universal unity for Human Reason, which finds conclusion in the Declaration of Human Rights. Schopenhauer has claimed that the universality of

communion. They are flow, current and vibration before being portraits. The black background that I resolutely use as a unity of place and time has a dual vocation. Aesthetically pleasing, it is also a congenital attachment to the Flemish baroque paintings, in the days when artists applied themselves to draw the faces of the jet-set as lifelike as possible, in order to transmit their referential image to posterity. Symbolic, it represents the mysterious darkness from which we appear and to which we will return after having taken forms. Not just one form, but an infinity. A quantity of fleeting appearances. Temporary expressions of one single reality that changes physiognomy after a metamorphosis of the identical. Behind the painted faces, the made-up faces, the adorned faces, the tattooed faces… stand people who are close to us, individuals driven by the same emotions. Beneath the cultural signs and marks of belonging — that first capture our attention by their exotic load — spring an ineffable sense of unity. Signs can vary; the signified remains the same from one society to another. Alongside the portrayal, there is a constant, as if beyond the inclinations inherent to space and time, there is a desire of being, serving an agreement [perhaps objective, perhaps magical] through which everything seems connected. Could it be that something evoked by Paul Ricoeur, making human beings identify as human, through an ethical desire, and which should earn them unconditional respect, no matter what their age, gender, religion, social condition or ethnic origins? An occidental idea of universal unity for Human Reason, which finds conclusion in the Declaration of Human Rights. Schopenhauer has claimed that the universality of  phenomena, so diverse in their representation, has one single essence, which in its most tangible form is called will. A quality that he extends throughout reality as a whole. “It exists,” he writes, “in a higher degree in the vegetable than in the mineral, and in the animal than in the plant.” This is also what Diderot had brilliantly sensed when he wrote, during the Enlightenment: “What does one form or another matter. Being born, living and passing, is changing forms. Each form has its own happiness and sadness[…]from the elephant to the flea, and from the flea to the molecule.” Bergson, on his part, spoke of a conscience of the universe: the Living, of which man would be a mere avatar. And Nietszche – to only mention him – imagined that the organic, psychological and inanimate worlds all followed the same and unique will. The philosophers teach us to replace ourselves in the global creation of life – not only human diversity, but also animal and vegetable diversity – and to ponder that we have something in common with the cosmos. The same profusion of shapes can be observed everywhere as if a single will or single mechanism was at work both among fireflies and stars. You could therefore claim – under cover of philosophy – that diversity is a necessary expression of universality. Entangled in universal laws, the individual would possess two physiognomies both essential, necessary, inseparable and foundational. He would be one shape captured in an instant, a representation, underpinned by a will to belong, a reason. The first would be situated in space, in time, and also in plurality; the second would always be one and indivisible in each beholder. The principal of diversity supposes these two aspects.

phenomena, so diverse in their representation, has one single essence, which in its most tangible form is called will. A quality that he extends throughout reality as a whole. “It exists,” he writes, “in a higher degree in the vegetable than in the mineral, and in the animal than in the plant.” This is also what Diderot had brilliantly sensed when he wrote, during the Enlightenment: “What does one form or another matter. Being born, living and passing, is changing forms. Each form has its own happiness and sadness[…]from the elephant to the flea, and from the flea to the molecule.” Bergson, on his part, spoke of a conscience of the universe: the Living, of which man would be a mere avatar. And Nietszche – to only mention him – imagined that the organic, psychological and inanimate worlds all followed the same and unique will. The philosophers teach us to replace ourselves in the global creation of life – not only human diversity, but also animal and vegetable diversity – and to ponder that we have something in common with the cosmos. The same profusion of shapes can be observed everywhere as if a single will or single mechanism was at work both among fireflies and stars. You could therefore claim – under cover of philosophy – that diversity is a necessary expression of universality. Entangled in universal laws, the individual would possess two physiognomies both essential, necessary, inseparable and foundational. He would be one shape captured in an instant, a representation, underpinned by a will to belong, a reason. The first would be situated in space, in time, and also in plurality; the second would always be one and indivisible in each beholder. The principal of diversity supposes these two aspects.  Without representation, it would be only utopia; without reason it would be but dissemblance. In order to exist, diversity needs a common ground, a canvas stretching over space and time, from which it distinguishes itself and by which it is prolonged. But this diversity would be commonplace if it wasn’t inherent in something more profound that reveals it and that you could readily call dignity, even if Bergson doesn’t hesitate to call it the mystical, in the sense that it calls for a psycho-spiritual type of wisdom. I have, during my travels, had the opportunity to come across, on a backstreet, at a marketplace, in isolated temples or at the heart of a desert, some remarkable human beings. The most fascinating ones were neither rich, nor famous. Some seemed extremely poor. The demonstration of their interior dimension was their wealth. Their way of looking at me, both attentive and indifferent, present and absent, full and empty, seemed to convey at what point everything has value without anything being important. Non-verbal communication that an unspeakable force mysteriously established beyond culture, distance and system, through a sort of silent exchange of experience of what I like to call Soul because that is where, if it exists, a true vision could be expressed. It is this self-esteem that I have endeavoured to capture, beyond social imperatives and contingent moods, trying intuitively to establish, between the subject and myself, a well-meaning and trusting climate that has the power to penetrate intimacy to grasp the most important. In this manner, I return to them, in a moment of exchange, the look that they give me. You could agree with Merleau Ponty that ”Man is a mirror for Man” in the sense that the other reveals certain blind spots of our own vision. Could we

Without representation, it would be only utopia; without reason it would be but dissemblance. In order to exist, diversity needs a common ground, a canvas stretching over space and time, from which it distinguishes itself and by which it is prolonged. But this diversity would be commonplace if it wasn’t inherent in something more profound that reveals it and that you could readily call dignity, even if Bergson doesn’t hesitate to call it the mystical, in the sense that it calls for a psycho-spiritual type of wisdom. I have, during my travels, had the opportunity to come across, on a backstreet, at a marketplace, in isolated temples or at the heart of a desert, some remarkable human beings. The most fascinating ones were neither rich, nor famous. Some seemed extremely poor. The demonstration of their interior dimension was their wealth. Their way of looking at me, both attentive and indifferent, present and absent, full and empty, seemed to convey at what point everything has value without anything being important. Non-verbal communication that an unspeakable force mysteriously established beyond culture, distance and system, through a sort of silent exchange of experience of what I like to call Soul because that is where, if it exists, a true vision could be expressed. It is this self-esteem that I have endeavoured to capture, beyond social imperatives and contingent moods, trying intuitively to establish, between the subject and myself, a well-meaning and trusting climate that has the power to penetrate intimacy to grasp the most important. In this manner, I return to them, in a moment of exchange, the look that they give me. You could agree with Merleau Ponty that ”Man is a mirror for Man” in the sense that the other reveals certain blind spots of our own vision. Could we  possibly use the young 14-year-old as a model, to whom Professor Cheselden gave back his eyesight by performing, for the very first time, a cataract operation in 1728. He said, as noted by the doctor in Philosophical transactions that for the child, “each new object was a new delight, and the pleasure was so intense that he would have liked other words to express it.” His long intimacy with darkness had prepared him, in short, not to see the world, but to see the world reveal itself. If seeing is learning, we should remember that this learning is always to be recommenced. May the people who, usually, look at images with an eye clouded by habit, suddenly open their eyes in a fashion that exceeds the ordinary, and they will find sublime what had become only stale. “Having a philosophical mind – claims Schopenhauer – is to be able to marvel at ordinary events[…], making a subject of study all what is the most ordinary.” It is no doubt for this reason that certain people, gifted, perhaps, with a particular talent, or deprived perhaps of certain aptitudes, prefer feeding off mutations of life and – as Blaise Pascal recommended – “contemplate in silence the miracles that nature has offered to you rather than looking them up with presumption.” Also certain that our essential role is to marvel at the universe, Louis Pauwels concludes that: “He who has been able to marvel, even if he is one day crushed by the world, has known that it was useful and good to be a man.” It is probably these people who make Earth inhabitable.

possibly use the young 14-year-old as a model, to whom Professor Cheselden gave back his eyesight by performing, for the very first time, a cataract operation in 1728. He said, as noted by the doctor in Philosophical transactions that for the child, “each new object was a new delight, and the pleasure was so intense that he would have liked other words to express it.” His long intimacy with darkness had prepared him, in short, not to see the world, but to see the world reveal itself. If seeing is learning, we should remember that this learning is always to be recommenced. May the people who, usually, look at images with an eye clouded by habit, suddenly open their eyes in a fashion that exceeds the ordinary, and they will find sublime what had become only stale. “Having a philosophical mind – claims Schopenhauer – is to be able to marvel at ordinary events[…], making a subject of study all what is the most ordinary.” It is no doubt for this reason that certain people, gifted, perhaps, with a particular talent, or deprived perhaps of certain aptitudes, prefer feeding off mutations of life and – as Blaise Pascal recommended – “contemplate in silence the miracles that nature has offered to you rather than looking them up with presumption.” Also certain that our essential role is to marvel at the universe, Louis Pauwels concludes that: “He who has been able to marvel, even if he is one day crushed by the world, has known that it was useful and good to be a man.” It is probably these people who make Earth inhabitable.

Intervention occurred during a meeting organized by UNESCO on the theme of Cultural Diversity.